Infrastructure as Code for the Mainframe

When a critical application update requires new infrastructure, such as additional storage, network configuration changes, or middleware adjustments, how long does your mainframe team wait? In many organizations, what takes minutes in cloud environments can stretch to days or weeks on the mainframe. This is not a technology limitation. It’s a process problem that mainframe infrastructure automation can solve.

The mainframe community has made significant strides in adopting DevOps practices for application development. Build automation, continuous integration, and automated testing are becoming standard practices. But application agility means little if infrastructure changes remain bottlenecked by manual processes and ticket queues.

The solution lies in applying the same DevOps principles to infrastructure that we’ve successfully applied to applications. This means standardization, automation, and treating infrastructure definitions as code. While the journey presents unique challenges, particularly around tooling maturity and organizational culture, the mainframe platform is ready for this evolution. This article explores how to bring infrastructure management into the DevOps era.

Standardization and automation of infrastructure

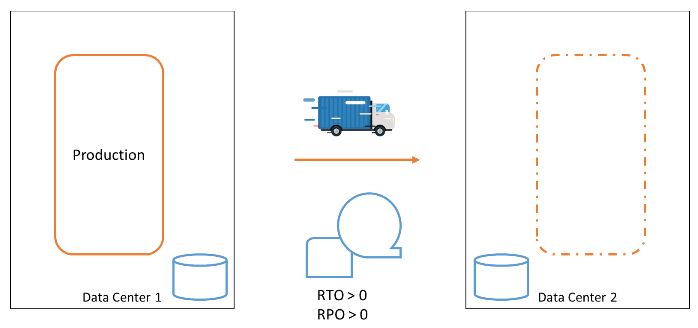

Like the build and deploy processes, all infrastructure provisioning must be automated to enable flexible and instant creation and modification of infrastructure for your applications.

Automation is only possible for standardized setups. Many mainframe environments have evolved over the years. A practice of rigorously standardized infrastructure setups was likely at the root of the setup. However, cleaning up is not generally a forte of IT departments in many organizations. A platform with a history as long as the mainframe often suffers even more from such a lack of cleanliness.

Standardization, legacy removal, and automation must be part of moving an IT organization toward a more agile way of working.

Infrastructure as Code: Principles and Practice

When infrastructure setups are standardized and automation is implemented, the code that automates infrastructure processes must be created in a similar manner to applications-as-code. There is no room anymore to do things manually. Everything should be codified.

Just as CI/CD pipelines are the code bases for the application creation process, infrastructure pipelines are the basis for creating reliable infrastructure code. Definitions of the infrastructure making up the environment must be treated like code and managed in a source code management system, where they can be properly versioned. The code must be tested in a test environment before deployment to production.

In practice, we see that this is not always possible yet. We depend on infrastructure suppliers for hardware, operating systems, and middleware. Not all hardware and middleware software are equipped with sufficient automation capabilities. Instead, these tools depend on human processes. Suppliers should turn their focus from developing sleek user interfaces to providing modern, most likely declarative, interfaces that allow for handling the tools in an infra-as-code process.

A culture change

In many organizations, infrastructure management teams are among the last to adopt agile working methods. They have always been so focused on keeping the show on the road that the risks of continuity disruptions have prevented management from having teams focus on development infrastructure-as-code.

Also, the infrastructure staff are often relatively conservative when it comes to automating their manual tasks. Usually not because they do not want it, but because they are so concerned about disruptions that they would rather get up at 3 a.m. to make a manual change than risk a programming mistake in the automation infra-as-code solution.

When moving towards infrastructure-as-code, the concerns of the infrastructure department management and staff should be taken seriously. Their continuity concerns can often be used to create extra robust infrastructure as a code solution. What I have seen, for example, is that staff do not just worry about creating infra-as-code changes but are most concerned about scenarios in which something could go wrong. Their ideas for rolling back changes have often been eye-opening toward a reliable solution that not only automates happy scenarios but also caters to unhappy scenarios.

However, the concern for robustness is not an excuse for keeping processes as they are. Infrastructure management teams should also recognize that there is less risk in relying on good automation than on individuals executing complex configuration tasks manually.

The evolving tooling landscape

The tools available for the mainframe to support infrastructure provisioning are emerging and improving quickly, yet they are still incoherent. Tools such as z/OSMF, Ansible, Terraform, and Zowe can play a role, but a clear vision-based architecture is missing. Work is ongoing at IBM and other software organizations to extend this lower-level capability and integrate it into cross-platform infrastructure provisioning tools such as Kubernetes and OpenShift. Also, Ansible for z/OS is quickly emerging. There is still a long way to go, but the first steps have been made.

Conclusion

The path to infrastructure-as-code on the mainframe is neither instant nor straightforward, but it’s essential. As application teams accelerate their delivery cycles, infrastructure processes must keep pace. The good news is that the fundamental principles are well established, the initial tooling exists, and early adopters are proving it works.

Success requires three parallel efforts: technical standardization to enable automation, cultural transformation to embrace change safely, and continuous pressure on vendors to provide automation-friendly interfaces. These don’t happen sequentially. They must advance together.

Start by assessing your current state. Inventory your infrastructure processes and identify which are already standardized and repeatable. Then choose one well-understood, frequently performed infrastructure task and automate it end to end, including rollback scenarios. Most importantly, engage your infrastructure team early. Their operational concerns will make your automation more robust, not less.

The mainframe has survived and thrived for decades by evolving. Infrastructure as code is simply the next evolution, ensuring the platform remains competitive in an increasingly agile world.

The mainframe has survived and thrived for decades by evolving. Infrastructure as code is simply the next evolution, ensuring the platform remains competitive in an increasingly agile world.

Getting started: your first IaC step

- Inventory your infrastructure processes

- Identify one standardized, frequently performed task

- Automate it end to end including rollback

- Engage your infrastructure team early

- Measure before and after: time, errors, incidents

Are you already on this journey? I’d love to hear where your organization stands— leave your thoughts below.

[Explore more mainframe modernization topics in my book Don’t Be Afraid of the Mainframe →](https://execpgm.org/dbaotm-the-book/)

This topic is covered in depth in my book Don’t Be Afraid of the Mainframe: The Missing Introduction for IT Leaders and Professionals—including practical frameworks for modernizing your mainframe infrastructure and development practices.

Learn more and order here →